Italy

Capitolo di Investitura Cavalieri Templari Dianum, OSMTHU

Il Balivato del Vallo di Diano ha tenuto una cerimonia di investitura,presieduta dal Priore Generale d’Italia OSMTHU, fratello Domenico Romano. Il Maestro Antonio era presente.

La cerimonia è stata ospitata dal Sindaco del Comune di Montesanto sulla Marcellana,in provincia di Salerno. Ha fatto seguito un agape fraterna.

Grand Prior of Italy of the OSMTHU installed in ceremony at the Convent della Pietá in Teggiano

Fr+ Domenico Romano, KGOTJ was installed as Grand Prior of Italy OSMTHU by Master António Paris this past 24 of June, day of the feast of Saint John the Baptist. The ceremony took place at the Convent della Pietá in Teggiano, is Salerno, Campania, Italy.

At the same ceremony new Bailiffs, Commanders and Grand Officers were installed, preparing the Grand Priory of Italy for the upcoming few years, leading a few projects to be announced in the contexto of the OSMTHU and the Templar Corps International.

Elezione del Principe Fra John Dunlap Gran Maestro dell’Ordine di Malta.

L’ Ordo Supremus Militaris Templi Hierosolimitani Universalis,Il Maestro Fr. Antonio Paris e il Consiglio MagistraleEsprimono grande soddisfazione per la elezione del Principe Fra John Dunlap Gran Maestro dell’Ordine di Malta.

Abbazia di Valvisciolo (Valvisciolo Abbey)

THE BEAUTIFUL ABBEY OF VALVISCIOLO (from the Italian “Valle dell’Usignolo”, Valley of the Nightingale) can be found between the gardens of Ninfa and the medieval town of Sermoneta, set against a backdrop of central Italy’s Lepini mountains.

Though we know very little about the earliest history of the abbey, it dates back to at least the 12th century, if not earlier. It was founded by Greek Basilian monks, and supposedly occupied by the Knights Templar in the 13th century. Legend has it that the Church’s architraves broke when the Templar Grand Master, Jacques de Molay, was burnt at the stake in 1314 (the Order had been suppressed and its members persecuted).

Traces of the abbey’s Templar past are believed to be subtle but very significant. A small templar cross is carved on the rose window on the façade, and the crack in the architrave is visible just underneath. More templar crosses have been spotted inside the church and on the ceilings of the cloister.

But one of the the abbey’s most interesting features is a very small carving on the wall that you walk past to enter the cloister. Sheltered by a transparent screen, you will find an unusual palindromic SATOR inscription. Its shape is not square, like those found elsewhere, but instead five concentric circles, crossed by five lines that divide the circles into five sectors that contain five letters. The palindrome is read in the following way in any direction: Sator Arepo Tenet Opera Rotas. The exact meaning of the inscription is unclear.

If you look carefully, you might also spot several carvings of Solomon’s knot (which has been interpreted as a metaphor of one’s esoteric journey in search of the self and of truth) and of the omphalos, the sacred center of the world. All of these carvings were discovered during restorations of the cloister and they might provide a mysterious testimony of the presence of the Knights Templar and of their spiritual symbolism.

Today, the Romanesque-Cistercian style abbey is home to Cistercian monks. The church has three naves divided by pillars and columns and bare walls, as the Cistercian tradition that avoids architectural splendor to emphasize the importance of the spiritual over the material.

in atlasobscura.com

Congratulations to the new Cardinals

From Master Antonio Paris, OSMTHU comments on a full day of engagements:

“Concistoro per la Creazione di Nuovi Cardinali. Basilica Papale di San Pietro. Con il Cardinale Pietro Parolin Segretario di Stato Vaticano.”

Congratulations also to Mons. Tolentino de Mendonça, new Portuguese Cardinal, currently heading the Vatican Library and the Vatican Secret Archive.

Mater Emeritus Antonio Paris Receives Malta Gran Cross

HE Antonio Paris, Master Emeritus OSMTHU, has received the Gran Cross of the Order of Saint John – Knights of Malta, during a ceremony in the Palace of the Order in La Valeta, from the hands of Grand Master Don Basilio Cali. The Grand Cross is the highest distinction given by the Order.

The Order of Saint John is one of the branches of the Order of the Hospital, that had headquarters in the Hospital of Saint John in Jerusalem at the times of the crusades.

This acts inaugurates a new cycle of cooperation and amity between the OSMTHU and the Order of Saint John, bringing, at the same time, Master Antonio Paris to the forefront of the Templar activity, after a few years of quiet retirement.

The Templar Globe congratulates Master Paris on this happy occasion.

Shroud of Turin ‘stained with blood from torture victim’, find researchers

The Shroud of Turin is stained with the blood of a torture victim, scientists have claimed.

Analysis of the linen cloth, purportedly used to bury Jesus after his crucifixion, contains “nanoparticles” of blood which are not typical of that of a healthy person, according to researchers.

Institute of Crystallography researcher Elvio Carlino, one of the authors of the report, said the particles are conducive with someone having been through “great suffering”.

“Our results point out that at the nanoscale a scenario of violence is recorded in the funeral fabric,” authors wrote in the scientific article, published in PLOS One.

“The consistent bound of ferritin iron to creatinine occurs in human organism in case of a severe polytrauma.”

Researchers believe the particles show a “peculiar structure, size and distribution”, which corroborates the theory that it was used as a burial cloth.

They also believe it contradicts previous theories that the shroud was made in medieval times.

Professor Giulio Fanti, one of the author’s of the research, said: “The presence of these biological nanoparticles found during our experiments point to a violent death for the man wrapped in the Turin Shroud.”

The cloth’s authenticity is highly contentious and divides religious opinion.

Some Christians believe the fabric – which is kept in the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Turin – is the burial shroud of Jesus of Nazereth, dating back over 2,000 years.

But previous scientific studies have suggested the cloth, which appears to be imprinted with the face of a man, may in fact be from the 13th or 14th century – centuries after Jesus is believed to have died.

One study found the cloth had been manufactured in India.

The research was published in US scientific journal PlosOne and is titled: “New Biological Evidence from Atomic Resolution Studies on the Turin Shroud.”

in independent.co.uk

Sicilian Vespers

On the morning of the 31st March, 1282, the Sicilian Vespers came to an end. The night of rioting and massacre which had started on Easter Monday proved crucial in the history of Sicily and also had a significant impact on the broader history of the Mediterranean in this period.

The revolt, which gets it name from the Hour of Vespers ceremony where it supposedly began, started on the 30th March and is believed to have been triggered by an Angevin soldier stopping a Palermitan woman outside the church of Santo Spirito di Palermo, to search her for weapons. Although details of the event of course vary depending on the source, it seems the soldier somehow offended the woman, triggering a riot against the Angevin-French among the local community.

Reflecting the deeply ingrained tensions in Sicily’s multicultural society, the rioting spread through Palermo and then the whole of the island. The local Sicilian population attacked and killed Angevin people wherever they could be found, going as far as murdering monks and nuns. The rioters supposedly used a simple test to determine the Sicilian population from Angevin. Anyone believed to have originated from Anjou was asked to say the word “ciciri”, something native French speakers could not do in a convincingly Sicilian accent.

In the annals of Medieval history, the revolt was a unique event. A spontaneous, popular uprising which affected political change. Following the night of the 30th to the 31st March the Angevin-French fled Sicily, and the people of the island eventually secured the support of the King of Aragon who sent troops there in August 1282. Although the revolt seemed to have occurred without any pre-planning, it is important to acknowledge that the uprising against the Angevin-French rulers was not completely without premeditation.

Since 1266 Charles of Anjou, with the support of the papacy, had ruled Sicily from Naples. Deeply unpopular in Sicily, Charles’ strict rule incurred the wrath of normal Sicilians, but his unpopularity in a broader context was just as significant. A group of Italian nobles, known as the Ghibellines, supported the authority of the Holy Roman Emperor rather than that of Charles and the papacy. Peter III of Aragon, a rival of Charles for the Neapolitan throne and one of the main beneficiaries of the uprising, also had a clear interest in altering the status quo on Sicily. The Night of the Sicilian Vespers may have been a demonstration of popular dissatisfaction at Charles’ tyranny, but there were a diverse range of groups with an interest in ending the Angevin presence on Sicily.

The revolt was followed by series of sea skirmishes and land battles between Angevin and Aragonese forces, sometimes referred to as the War of the Vespers. The fighting finally came to a close in 1302, with the Peace of Caltabellotta. The treaty saw Charles II, the son of Charles of Anjou, concede Sicily to King Frederick, a relative of Peter of Aragon. Sicily was now firmly under the sphere of Spanish influence, a situation which would persist for another five centuries.

Historians have since argued that the Sicilian Vespers, and the subsequent war, proved crucial in the failure of the crusades in the Eastern Mediterranean. Charles of Anjou and the Vatican had been planning to send troops to take Constantinople when the uprising started. The need to divert resources to Sicily put this campaign on hold. Although one of many factors which ultimately led to the failure of the crusades, it is not a coincidence that the fall of Acre in 1291, a pivotal defeat for Christians in the Middle East, took place during the War of the Vespers.

Indeed, the significance of events in Sicily in the broader context of Mediterranean history in this period can be seen in the theory that the Aragonese and Sicilian forces received financial support from Byzantine. Although the scope and nature of this support cannot be confirmed, it hints at the complex political workings of the period.

The Sicilian Vespers revolt was an expression of popular dissatisfaction at the harsh rule of Charles of Anjou over Sicily. This moment of rebellion by Sicilians however, can only be truly understood in the broader context of Medieval history.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons user: Enzian44

By: Daryl Worthington in newhistorian.com

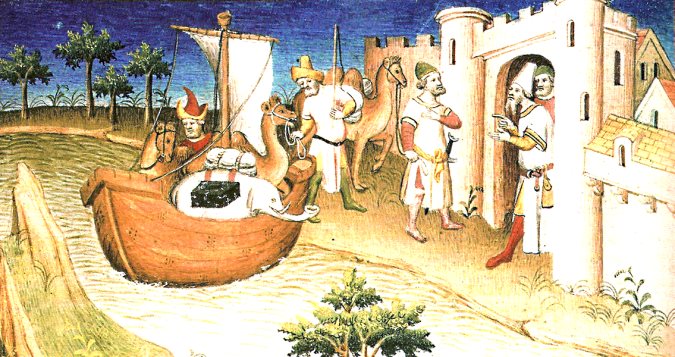

The Travels of Marco Polo

Originally dictated in a Genoese prison cell, ‘The Travels of Marco Polo’ straddles the line between travel literature and adventure story. The teller of the story, Marco Polo, claimed that the work was based completely on fact, compiled from his travels around the world. The book was hugely popular in Medieval Europe, despite being widely referred to as ‘The Million Lies’.

Marco Polo was not the first European to venture into Asia, but he traveled much further to the East than any before him, and, according to the book at least, became much more integrated into the cultures there. The real key to the work’s success is the imagination and energy put into the descriptions of Asia, Africa and the Mongol Empire. The work often seems fantastical, partly because some of the things Polo described were indeed made up, but also because the language used is so colourful it seems unbelievable.

The adventure to the East actually started when Nicolo and Maffeo Polo, Marco’s father and uncle, set off for Constantinople in 1260. From this journey they ventured into the lands of the Mongolian tribes, eventually reaching the court of Kublai Khan. The Polos returned to Europe, eventually arriving in their home city of Venice in 1269. Upon his return, Nicolo discovered he had a son, Marco Polo. The Polos, who had promised Kublai Khan they would come back to Mongolia with Catholic missionaries, eventually set off on their return to Asia with Marco and two Catholic friars, in 1271. Although the friars eventually gave up on the journey, the Polo’s returned to the Khan’s court, where Marco became a confidant of Kublai Khan.

Marco Polo remained in the Khan’s court for seventeen years, and was sent on a variety of missions and errands, allowing him to travel in previously uncharted territories. Through his service he explored much of what is now China, as well as venturing into India, and crossing over to Sri Lanka. A recently revealed map, attributed to Polo and signed for authenticity by his three daughters, is believed to sketch out the coast of Japan and Alaska. The origins and veracity of the map have not been confirmed, but some researchers have claimed that it proves Polo’s travels actually took him as far as the shores of North America.

‘The Story of Marco Polo’ details his experiences in this period of his life. It includes descriptions of the journey from Acre (in what is modern day Israel), through Persia and then onto the Khan’s palace in what is now Beijing. The Polos traveled over a series of overland trader’s routes, what would eventually become known as the Silk Road. As well as providing detailed descriptions of Polo’s experiences in the Khan’s court, the book is just as crucial for its depiction of the journey along the Silk Road, providing information on the cultures and landscapes the Polo family encountered.

Some critics question the validity of the text, pointing out that there is no mention of Polo in the detailed records of the Khan’s court from the thirteenth century. They also point out that despite Polo’s extensive stay and travels in Asia, he never made reference to major landmarks, such as the Great Wall, or distinctive cultural traits, such as eating with chopsticks or foot binding.

Polo himself eventually returned to Europe in 1295. He became involved in a conflict between Venice and Genoa, during which he was captured and imprisoned. While incarcerated he met Rustichello, a writer from Pisa who started to write down Polo’s stories.

Whether these stories were a complete fabrication, or just heavily embellished by Polo or Rustichello, they remain a fascinating document. The book was pivotal in shaping opinions on Asia and the Mongol Empire, long after its publication. Whether the book is factually accurate or not, it cannot be denied that the stories within, as well as the history of Polo himself, make it a fascinating read.

By: Daryl Worthington in newhistorian.com

Visitor General of the OSMTHU to cease functions

Starting January 1st, 2016, Fr+ Roman Vertovec is ceasing functions as the Visitor General of the OSMTHU. It’s with a great sense of pride that the Magisterial Council acknowledges the high quality of its members, frequently chosen to lead Templar initiatives and groups elsewhere in the neo-Templar world. The Magisterial Council was informed that Fr+ Roman will lead a new group composed of the Priory of Italy (Napolitan branch), the Priory of Croatia and the Priory of Bulgaria, having already been installed as the group’s leader in Zagreb.

The OSMTHU and the Magisterial Council wishes Fr+ Roman Vertovec the best in this new courageous task. God, undoubtably, will bless all those who act with a pure heart.

Luis de Matos

Chancellor and Interim Master

OSMTHU

For more information on the OSMTHU, please visit the official site at: templarsosmthu.wordpress.com

Medieval European Perceptions of Islam

In 1087, a joint Pisan and Genoese force attacked the North African town of Mahdia, located in modern-day Tunisia. Christian forces returned to Italy triumphantly and used their spoils of war to construct commemorative churches.

A number of Arabic and Latin sources from the time testify to the events surrounding the raid of Mahdia.

One of the most important Latin sources is the poem Carmen in Victoriam Pisanorum, ‘Song for the Triumph of the Pisans’. The Carmen, written by a Pisan cleric only months after the raid, commemorates the expedition.

It has often been argued that the raid on Mahdia – conducted under the banner of St. Peter against a Muslim ruler – was a direct precursor to the First Crusade which followed eight years later. The Carmen is often viewed as providing context for the development of a crusading ideology in the eleventh century.

A pioneering new study has taken a fresh look at the Carmen. Matt King, a PhD student in the Department of History at the University of Minnesota, has been studying the Carmen as a means of understanding Christian perceptions of Islam.

“An examination of this text will allow historians to consider Latin Christian perspectives on Islam and its adherents during the period immediately preceding the First Crusade,” King writes in his article, published in Hortulus, a graduate journal on medieval studies.

It is usually suggested that Pisan interests in North Africa were primarily commercial, with military activities receiving less attention. King argues that there was a certain level of coexistence and cooperation between Pisa and Islamic states, while the Carmen reveals a different side of the story where religiously-charged rhetoric could be applied to justify violent ends.

The Mahdia raid can be located in a wider context of Pisan military activities in North Africa. Pisa had been involved in military actions against Muslims throughout the eleventh century; briefly seizing the city of Bone in 1034 and helping the Norman Robert Guiscard in his conquest of Sicily in 1063.

“The author of the Carmen was thus writing in the midst of conflicts between burgeoning Italian commercial powers and Muslim states in the Mediterranean,” King notes.

Importantly, the Carmen makes frequent Old Testament references in an effort to locate Pisan activity in a Biblical tradition. Within this framework, the inhabitants of Mahdia take the form of Old Testament villains who feel the wrath of God. In contrast, King argues, the Pisans are a Gideon/David/Moses combination who, through the favour of God, are able to defeat their adversary.

“Such a description makes clear the deep religious roots that run throughout this story,” King notes. “In this narrative, it is impossible to separate the sacking of Mahdia or the author’s perception of Islam from this ancient narrative.”

The portrayal of Islam in the Carmen is a multi-faceted one. Pisan attacks are understood as an epic confrontation, similar to the Old Testament and classical tales. Further, the doctrine of the Muslim inhabitants of Mahdia is portrayed as a form of heretical Christianity. Taken together, these depictions of Muslim Africa reveal a medieval Latin understanding of the area as a place and people of the utmost evil.

King notes that the Carmen is, however, a triumphant poem. The author is consciously contextualising the Pisan-Genoese raid in a tradition of God-willed triumph. Simply taking the Carmen’s portrayal of Islam at face value, therefore, may misrepresent the Latin understanding of Islam.

“If we cautiously take the Carmen as indicative of general trends in Pisan perceptions of Islam and Africa,” King concludes, “we thus can see an image of Pisa as a city with some knowledge of medieval Ifriqiya and as one that used this knowledge to nurture some image of righteous war against Muslims.”

For more information: www.hortulus-journal.com

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons user: DrFO.Jr.Tn

By: Adam Steedman Thake in newhistorian.com

Rome’s Colosseum Used As Condominiums in the Medieval Era

The grand Roman Colosseum, one of the most iconic remains of Ancient Rome, transformed from being a land that hosted blood and gore shows to being a land that hosted condominiums in the medieval era. According to the latest archaeological investigations made by experts from the Toma Tre University together with students from the American University of Rome, new evidence now shows that the Romans used to live in the Colosseum from the 9th century until the year 1349 when the iconic monument was terribly damaged by a major earthquake.

This fact was uncovered after a 3-week excavation that uncovered a few arched entrances which lead into the arena. Archaeologists discovered the foundations of a 12th century wall that was used to enclose a particular property in the Colesseum, potshards and terracotta sewage pipes. According to Rossella Rea, the Director of the Roman Colosseum, these excavations allowed archaeologists to identify a complete housing lot from the Medieval era. It is believed that this unusual condominium also consisted of workshops and stables and that area within the Colosseum was rented out by friars of the Santa Maria Nova Convent who had control of the monument.

Further research also indicated that all houses opened onto the area where the gladiators once used to fight. Professor Riccardo Santangeli Valenzani, teaching medieval archaeology at the Roma Tra University, believes that the area that once hosted glorious gladiator battles was transformed into a common space for the Romans living there in the medieval era. It is believed that this courtyard was buzzing with goods, animals and people. Archaeologists also uncovered cooking pottery along with the figurine of a tiny monkey that was carved from ivory. It is believed that this piece was used as a pawn in a chess set during the medieval era.

The Roman Colosseum dates back to the year AD 72 when it was built by the great emperor Vespasian on the bed of a drained lake. It is considered to be the most popular remains of Ancient Rome. Many might not know this, but the Amphitheatre was actually opened in the year AD 80 by Titus, Vespasian’s son. This amphitheatre was inaugurated with a festival that lasted for 100 days and consisted of naval battles, fights and gladiatorial combats.

Another reason why the Colosseum became so popular over the centuries was the fact that it survived 3 major earthquakes as well as a huge fire. It transformed into a garbage dump after emperor Honorius banned bloody gladiatorial combats as well as a stone quarry for buildings such as the St. Peter’s Basilica. The recent excavations have uncovered yet another piece of history for the Roman Colosseum.

The Roman Colosseum is currently undergoing a $43 million restoration and cleaning project, the cost of which is being sponsored by Tod’s, a popular leather bag company in Italy. According to Rea, the dig should continue in the year 2015 when the second phase of the cleaning and restoration starts. More and more mysteries pertaining to the most visited monument of Italy are expected to be uncovered during the second phase of excavations.

By: Tajirul Haque in newhistorian.com

Centuries of Italian History Are Unearthed in Quest to Fix Toilet

By JIM YARDLEY

LECCE, Italy — All Luciano Faggiano wanted when he purchased the seemingly unremarkable building at 56 Via Ascanio Grandi was to open a trattoria. The only problem was the toilet.

Sewage kept backing up. So Mr. Faggiano enlisted his two older sons to help him dig a trench and investigate. He predicted the job would take about a week.

If only.

“We found underground corridors and other rooms, so we kept digging,” said Mr. Faggiano, 60.

His search for a sewage pipe, which began in 2000, became one family’s tale of obsession and discovery. He found a subterranean world tracing back before the birth of Jesus: a Messapian tomb, a Roman granary, a Franciscan chapel and even etchings from the Knights Templar. His trattoria instead became a museum, where relics still turn up today.

Italy is a slag heap of history, with empires and ancient civilizations built atop one another like layers in a cake. Farmers still unearth Etruscan pottery while plowing their fields. Excavation sites are common in ancient cities such as Rome, where protected underground relics have for years impeded plans to expand the subway system.

Situated in the heel of the Italian boot, Lecce was once a critical crossroads in the Mediterranean, coveted by invaders from Greeks to Romans to Ottomans to Normans to Lombards. For centuries, a marble column bearing a statue of Lecce’s patron saint, Orontius, dominated the city’s central piazza — until historians, in 1901, discovered a Roman amphitheater below, leading to the relocation of the column so that the amphitheater could be excavated.

“The very first layers of Lecce date to the time of Homer, or at least according to legend,” said Mario De Marco, a local historian and author, noting that invaders were enticed by the city’s strategic location and the prospects for looting. “Each one of these populations came and left a trace.”

Severo Martini, a member of the City Council, said archaeological relics turn up on a regular basis — and can present a headache for urban planning. A project to build a shopping mall had to be redesigned after the discovery of an ancient Roman temple beneath the site of a planned parking lot.

“Whenever you dig a hole,” Mr. Martini said, “centuries of history come out.”

Ask the Faggiano family. Mr. Faggiano planned to run the trattoria on the ground floor and live upstairs with his wife and youngest son. Before they started digging, Mr. Faggiano’s oldest son, Marco, was studying film in Rome. His second son, Andrea, had left home to attend college. The building was seemingly modernized, with clean white walls and a new heating system.

“I said, ‘Come, I need your help, and it will only be a week,’ ” Mr. Faggiano recalled.

But one week quickly passed, as father and sons discovered a false floor that led down to another floor of medieval stone, which led to a tomb of the Messapians, who lived in the region centuries before the birth of Jesus. Soon, the family discovered a chamber used to store grain by the ancient Romans, and the basement of a Franciscan convent where nuns had once prepared the bodies of the dead.

If this history only later became clear, what was immediately obvious was that finding the pipe would be a much bigger project than Mr. Faggiano had anticipated. He did not initially tell his wife about the extent of the work, possibly because he was tying a rope around the chest of his youngest son, Davide, then 12, and lowering him to dig in small, darkened openings.

“I made sure to tell him not to tell his mama,” he said.

His wife, Anna Maria Sanò, soon became suspicious. “We had all these dirty clothes, every day,” she said. “I didn’t understand what was going on.”

After watching the Faggiano men haul away debris in the back seat of the family car, neighbors also became suspicious and notified the authorities. Investigators arrived and shut down the excavations, warning Mr. Faggiano against operating an unapproved archaeological work site. Mr. Faggiano responded that he was just looking for a sewage pipe.

A year passed. Finally, Mr. Faggiano was allowed to resume his pursuit of the sewage pipe on condition that heritage officials observed the work. An underground treasure house emerged, as the family uncovered ancient vases, Roman devotional bottles, an ancient ring with Christian symbols, medieval artifacts, hidden frescoes and more.

“The Faggiano house has layers that are representative of almost all of the city’s history, from the Messapians to the Romans, from the medieval to the Byzantine time,” said Giovanni Giangreco, a cultural heritage official, now retired, involved in overseeing the excavation.

City officials, sensing a major find, brought in an archaeologist, even as the Faggianos were left to do the excavation work and bear the costs. Mr. Faggiano also engaged in extensive research into the eras tiered below him. The two older sons, Marco and Andrea, found their lives interrupted by their father’s quest.

“We were kind of forced to do it,” said Andrea, now 34, laughing. “I was going to university, but then I would go home to excavate. Marco as well.”

Mr. Faggiano still dreamed of a trattoria, even if the project had become his white whale. He supported his family with rent from an upstairs floor in the building and income on other properties.

“I was still digging to find my pipe,” he said. “Every day we would find new artifacts.”

Years passed. His sons managed to escape, with Andrea moving to London. City archaeologists pushed Mr. Faggiano to keep going. His own architect advised that digging deeper would help clear out sludge below the planned bathroom, should he still hope to open his trattoria. He admits he also became obsessed.

“At one point, I couldn’t take it anymore,” he recalled. “I bought cinder blocks and was going to cover it up and pretend it had never happened.

“I don’t wish it on anyone.”

Today, the building is Museum Faggiano, an independent archaeological museum authorized by the Lecce government. Spiral metal stairwells allow visitors to descend through the underground chambers, while sections of glass flooring underscore the building’s historical layers.

His docent, Rosa Anna Romano, is the widow of an amateur speleologist who helped discover the Grotto of Cervi, a cave on the coastline near Lecce that is decorated in Neolithic pictographs. While taking an outdoor bathroom break, the husband had noticed holes in the ground that led to the underground grotto.

“We were brought together by sewage systems,” Mr. Faggiano joked.

Mr. Faggiano is now satisfied with his museum, but he has not forgotten about the trattoria. A few years into his excavation, he finally found his sewage pipe. It was, indeed, broken. He has since bought another building and is again planning for a trattoria, assuming it does not need any renovations. He has no plans to lift a shovel.

“I still want it,” he said of the trattoria. “I’m very stubborn.”

in New York Times

Pope confirms visit to Shroud of Turin; new evidence on shroud emerges

Pope Benedict XVI confirmed his intention to visit the Shroud of Turin when it goes on public display in Turin’s cathedral April 10-May 23, 2010.

Cardinal Severino Poletto of Turin, papal custodian of the Shroud of Turin, visited the pope July 26 in Les Combes, Italy, where the pope was spending part of his vacation. The Alpine village is about 85 miles from Turin.

The cardinal gave the pope the latest news concerning preparations for next year’s public exposition of the shroud and the pope “confirmed his intention to go to Turin for the occasion,” said the Vatican spokesman, Jesuit Father Federico Lombardi, in a written statement July 27.

The specific date of the papal visit has yet to be determined, the priest added.

The last time the Shroud of Turin was displayed to the public was in 2000 for the jubilee year. The shroud is removed from a specially designed protective case only for very special spiritual occasions, and its removal for study or display to the public must be approved by the pope.

The shroud underwent major cleaning and restoration in 2002.

According to tradition, the 14-foot-by-4-foot linen cloth is the burial shroud of Jesus. The shroud has a full-length photonegative image of a man, front and back, bearing signs of wounds that correspond to the Gospel accounts of the torture Jesus endured in his passion and death.

The church has never officially ruled on the shroud’s authenticity, saying judgments about its age and origin belonged to scientific investigation. Scientists have debated its authenticity for decades, and studies have led to conflicting results.

A recent study by French scientist Thierry Castex has revealed that on the shroud are traces of words in Aramaic spelled with Hebrew letters.

A Vatican researcher, Barbara Frale, told Vatican Radio July 26 that her own studies suggest the letters on the shroud were written more than 1,800 years ago.

She said that in 1978 a Latin professor in Milan noticed Aramaic writing on the shroud and in 1989 scholars discovered Hebrew characters that probably were portions of the phrase “The king of the Jews.”

Castex’s recent discovery of the word “found” with another word next to it, which still has to be deciphered, “together may mean ‘because found’ or ‘we found,’“ she said.

What is interesting, she said, is that it recalls a passage in the Gospel of St. Luke, “We found this man misleading our people,” which was what several Jewish leaders told Pontius Pilate when they asked him to condemn Jesus.

She said it would not be unusual for something to be written on a burial cloth in order to indicate the identity of the deceased.

Frale, who is a researcher at the Vatican Secret Archives, has written a new book on the shroud and the Knights Templar, the medieval crusading order which, she says, may have held secret custody of the Shroud of Turin during the 13th and 14th centuries.

She told Vatican Radio that she has studied the writings on the shroud in an effort to find out if the Knights had written them.

“When I analyzed these writings, I saw that they had nothing to do with the Templars because they were written at least 1,000 years before the Order of the Temple was founded” in the 12th century, she said.

By Carol Glatz

Catholic News Service

The rich history of L’Aquila

Although L’Aquila is in a captivating setting, it has never been a priority for tourists. It is a discreet, traditional and very provincial Italian city between Rome and the Adriatic sea about an hour’s drive east of the capital.

A city rich in history, art and culture. It is built on the same plan and layout as Jerusalem. Both are on a hill, both are located at the same height above sea level and there are many other similarities. When walking around L’Aquila and looking into open doorways, one would discover beautiful hidden renaissance courtyards.

The majority of these courtyards have been destroyed by the earthquake.

Main crossroad

In the Middle Ages L’Aquila was on the road between two extremely powerful, important trading towns, Naples and Florence. It was famous for its rich fair where sheep, wool, milk, cheese, cattle, leather, cloth, almonds and saffron were traded. Later important noble families from Tuscany came to Abruzzo to take advantage of its produce and so it became the rich hinterland of Tuscany.

This main road connecting south and central Italy, called Via degli Abruzzi, was the safest road between Tuscany and the powerful kingdom of Naples and Sicily. The only other route was through the Vatican States, where dangerous outlaws populated the roads.

Transumanza

From at least 300 BC the open space on the hill where the basilica of S. Maria di Collemaggio would be built was the meeting point for the annual transumanza, the long trek of tens of thousands of sheep and hundreds of shepherds from the hot plains in the south to the high plain of Abruzzo and back. In those days sheep, with their by-products of cheese, milk and wool, were of utmost importance for survival.

When the summer heat started on the bare plains of southern Italy, the transumanza would begin – sheep, dogs, shepherds and butteri, the only men on horseback. These were the men who would milk the sheep early in the morning and make the cheese that would be sold along the way. Together they would make their long 15-day walk across the mountains and hills up to the cool plain in Abruzzo, to Campo Imperatore 1,900 m above sea level, one of the largest plains in Europe, where the aquile (eagles) fly high. They were allowed on the plain after 5 June and had to be gone by 15 September each year. These regulations were established in Roman times.

The shepherds were given a flask of olive oil before they left and a loaf of bread every day but they were not allowed to indulge in fresh sheep’s milk or cheese along the journey. They were paid according to the number of sheep they had been assigned before setting off and the number they delivered alive.

The outstanding beauty of the basilica of S. Maria di Collemaggio. It was built in 1287 by Pietro da Morrone, a hermit living in the Morrone mountains in Abruzzo in the days when the region was known for its hermits and witches. Originally on a hill to the southwest of L’Aquila, but now in the centre of the city, it is a masterpiece of Abruzzo Romanesque, with a pink and white façade and 14th-century frescos. It has a most beautifully sculptured rose window above its main entrance and a majestic pure Gothic interior. A Holy Door, similar to the one in St Peter’s in Rome, was added to the church at the beginning of the 14th century.

Only the façade and side walls stand today as they were protected by scaffolding being used for restoration. The Holy Door was not touched and is still standing.

Templars

The Templars, known for their white flag with a red cross, started off as guards who escorted and protected pilgrims to the Holy Land. They financed the building of the basilica of S. Maria di Collemaggio, supplying Pietro da Morrone with a team of expert artisans and architectural plans, which meant that the basilica was built in record time.

Pietro da Morrone, later Pope Celestine V. Pietro da Morrone was crowned pope on 29 August 1294 in the basilica he built. They say 200,000 people attended his coronation, a very large number for those days. One hundred and seven days later he resigned and went back to being a hermit in the mountains. He was eventually arrested by his successor and long-time opponent, Pope Boniface VIII, and imprisoned near Anagni, south of Rome. He died there nine months later, possibly murdered. Pietro da Morrone was canonised in 1313 and several years later his body was transferred to the church he built in L’Aquila.

His body was not destroyed by the earthquake and is in safekeeping in the basilica of S. Maria di Collemaggio.

Perdonanza Celestiniana. This is a historical pageant evoking the extraordinary indulgence declared by Celestine V in L’Aquila on the night of his coronation as pope, which established that: “Whoever entered the basilica sincerely repentant and confessed one’s sins between the nights of 28-29 August would be absolved of all sins since baptism.” This ceremony has been repeated in the basilica of Collemaggio for 714 years.

Work has already started to restore the church so that the feast of Celestine’s indulgence can be repeated in August 2009. This objective will be achieved . . .

by Fabrizio G. Scalabrino