Day: August 16, 2007

Knights in white sashes

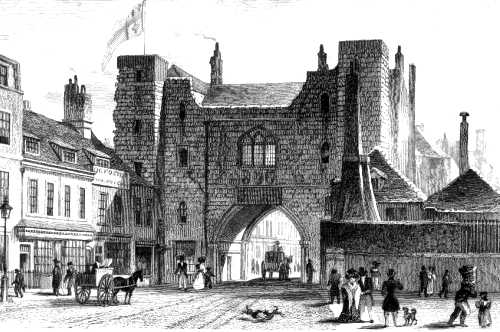

TUCKED away in Clerkenwell in the heart of old London, close to Smithfield meat market and ignored by office workers as they scurry past, is a remarkable link with the Crusades: it is St John’s Gate, which, with the nearby Grand Priory Church, is all that remains of the English headquarters of the Knights Hospitaller of St John of Jerusalem, one of the two great Crusader orders.

The other order, the Knights Templar, is better remembered because it was so viciously crushed, amid sensational false accusations of blasphemy, sodomy and heresy, by Philip of France and the Pope in the 14th century.

The Knights of St John were not suppressed – on the contrary, they were given some of the disgraced Templars’ property – but they changed their name over the centuries, as their main base moved from the Holy Land to Rhodes, then again to Malta; and their English Priory, along with all other monastic foundations, was dissolved by Henry VIII.

The Knights of Malta still exist as a Roman Catholic order, whereas the present English Order of St John, a 19th-century revival granted an order of chivalry by Queen Victoria, is now a non-denominational, charitable organisation that admits non-Christian members.

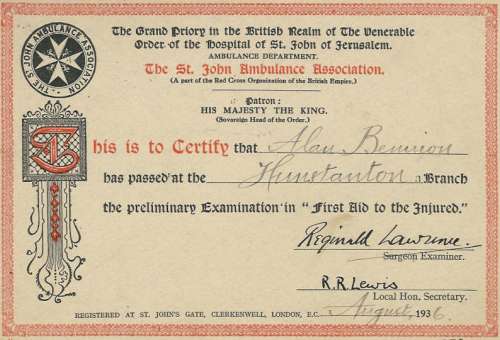

St John Ambulance Brigade vehicles and staff are such a familiar sight at public events that few of us stop to wonder why the brigade is so-called; in fact, it was created in 1877 by the Order of St John, which also founded the St John Opthalmic Hospital in Jerusalem five years later.

In the centuries between Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries and the revived English order’s purchase of St John’s Gate in 1874, the building had a chequered career – first as the office of Elizabeth I’s Master of the Revels; later as the coffee house where the artist Hogarth spent his early childhood (his father’s advertised boast that Latin was spoken at the coffee house seems to have discouraged, rather than drawn, patrons, and his business failed). The gatehouse then became the home and printworks of Edward Cave, publisher of the Gentleman’s Magazine. On the staff was the great Dr Johnson, who locked himself into a room to write without distraction.

A spell as the parish watch house followed, then, in the 19th century, the gatehouse became the Old Jerusalem Tavern. Somewhere along the way, as prints show, the stone building lost its crenulated roofline, but this has been restored and St John’s Gate today looks much as it did when rebuilt in 1504, with one significant difference: it has lost several feet in height, through the road surface having been built up over the centuries.

Adjoining it at right angles is an Edwardian extension in the same style, with a flamboyant, rooflit Chapter Hall and a fascinating museum of items relating to the Knights of St John’s history and the work of the St John Ambulance Brigade.

Objects on show include superb pieces of silver, such as a 17th-century shaving bowl the size of a washbasin; Majolica pharmacy jars; intricate wooden models of Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre, inlaid with ivory, ebony and mother-of-pearl; two panels of a fine Flemish triptych, marked with the arms of the 15th-century prior John Weston; the exquisitely illuminated Rhodes Missal, completed in 1504; and a cleverly designed late-19th-century litter, or hand-wheeled ambulance.

Although the medieval Knights of St John developed a military role as time went on – culminating in their conquest of Rhodes, which they ruled as a sovereign power for 200 years until 1522 – they began as hospitallers, pure and simple. Their great hospital in Jerusalem held 2,000 patients, Muslim and Jew as well as Christian, who were treated not just well, but luxuriously – provided with feather beds, the finest food and wine, daily washing with hot water and twice-weekly pedicures. Brothers would scour the streets of the city for people too sick to make their own way to the hospital, and for mothers and babies in need of care. The hospitallers believed that the poor represented the person of Christ, and were therefore to be venerated.

The lavish treatment of the sick was continued at their infirmaries in Rhodes, and later in Malta, where patients were fed from silver dishes and beakers. Malta was given to the order by Emperor Charles V, after Rhodes was conquered by the Turks under Suleiman the Magnificent in 1523. The Knights ruled Malta until Napoleon captured the island in 1798.

The English branch (or Langue, meaning tongue, as it is called) of the order was re-formed in 1827, with both Catholic and Protestant members. Harking back to the days of chivalry, it began as a Romantic movement, whose members did little more than make excursions along the Thames to dine at Kew or Greenwich. Only in the 1860s did the success of the newly formed Red Cross inspire members to provide a similar service for civilians at home, particularly industrial workers, and thus to find a role in the modern world.

Visitors to St John’s Gate can also see the Grand Priory Church. This now necessitates stepping out along the street, although the church was originally the focal point of the Priory’s enclosed 10-acre site. It is only a fraction of its original size, having lost its nave during Edward VI’s reign when Lord Protector Somerset used the stone to build his palace in the Strand. Lady Burleigh repaired what remained of the church and used it as her private chapel in the early 17th century. It was a Presbyterian meeting-house from 1706 until it was gutted during the Sacheverell Riots of 1710; repaired again, the building became an Anglican parish church until 1931, when it was finally given back to the Knights of St John – only to be gutted by bombing just 10 years later.

Now restored very simply and used for the order’s investitures, the church’s main interest lies below ground, where the beautiful 12th-century crypt has miraculously survived. Its nave of five bays is partly late Norman, partly in Transitional style, and there are two wonderful tombs: one topped by the skeletal figure of William Weston, the order’s last, pre-Reformation prior; the other of alabaster, bearing the effigy of Don Juan Ruiz de Vergara, 16th-century Proctor of Castile. At his feet nestles the effigy of a boy.

“His son?” I inquired naively. “I hope not!” replied curator Pamela Willis, laughing, “As a member of the order, Don Juan was supposed to be celibate. We believe the boy was his page.”

The Museum of the Order of St John (020 7324 4000, www.sja.org.uk) is in St John’s Gate, St John’s Lane, Clerkenwell, London EC1. Nearest Tube stations, Farringdon and Barbican. Museum open Monday- Friday, 10am-5pm; Saturday, 10am-4pm (closed bank holiday weekends). Admission free. Guided tours, taking in the gatehouse’s other rooms and Grand Priory Church, 11am and 2.30pm, Tuesday, Friday, Saturday.